The Value of Experience

Design and operation of a successful wood pellet plant boils down to experience and attention to detail, with a heavy focus on fiber.

John Swaan is the kind of guy a wood pellet operation wants on its team. With decades of experience in forest management, fiber logistics and pellet production, Swaan is armed with knowledge that can’t be acquired by reading any manual or textbook.

Having founded wood pellet manufacturer Pacific BioEnergy Corp. 30 years ago, Swaan has witnessed the success and demise of many operations. Perhaps a bit of consolation for those failed projects is that almost always, valuable knowledge has been gained. “Fairly complex lessons have been learned in the wood pellet industry in the past 30 years, and they are still being learned,” Swaan says. “This has provided us with guidance. The devil is really in the details, and the details really matter.”

By details, Swaan refers to everything from siting a plant to design, fiber preparation and understanding how it affects each plant component. Before any of that is considered, Swaan says the first matter of business is finding that niche experience, which he deems crucial. “There are two categories of developers—first, the small ones, who usually have their own ideas about how this should work and think that it looks relatively simple, so they do it their way,” he says. “Then, you have investors, who may hire a contractor, design/engineering firm and equipment suppliers. A lot of them may have huge balance sheets, but not a whole lot of expertise in this area, and then the plants end up not working and under litigation.”

When it comes to experience, Mid-South Engineering is one firm that has been involved in the industry for more than a decade, and has provided engineering services for the majority of large pellet facilities in the U.S., projects ranging from minor upgrades and troubleshooting, to complete facility design on both greenfield and brownfield projects, according to Scott Stamey, senior project manager. Like Swaan, Stamey emphasizes the importance of experience and expertise. “There are countless details in respect to the handling and process of biomass from the tree to the finished pellet, and overlooking these can negatively impact production and quality for years to come,” he says. “Major variables that can affect the design of a new facility or expansion include the range of raw material properties—present and future—sizing and drying process requirements, future expansion options, shipping and receiving logistics, level of automation, and any pellet quality requirements. Every project is different, so engineers must be sure to fully understand the owner’s needs and goals.”

Specifically, the first and perhaps most important detail to consider is feedstock, according to Swaan, and it should be the No. 1 focus in determining where and how a successful pellet plant should be placed.

Focus on Fiber

Fiber should be uniform and homogenous as presented to the pellet mill, Swaan reiterates. “This is a critical piece of understanding to make this successful—not only production itself, but it also has correlation on maintaining uptime, which is critical to your margins.”

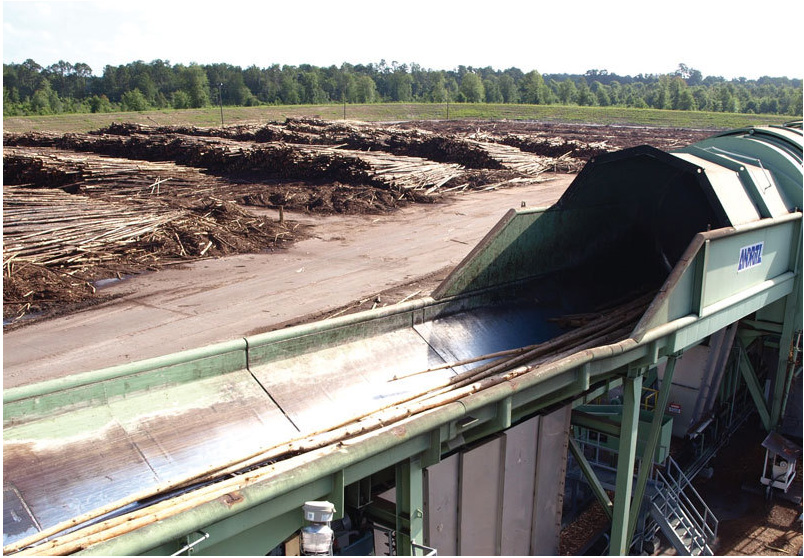

Justin Price, principal at Evergreen Engineering®, explains exactly how that consistency of fiber handling and moisture content can influence plant operations and end product. “Typically with pellet mills, we’re buying residuals—planar shavings, green sawdust, dry sawdust, chips and so on—all of those products and how they’re organized in your yard and fed into your systems, that’s going to impact your process,” he says. “You want to control the green fiber both in size and moisture content for a tighter consistency.”

That’s done through good screening and fiber-sizing mechanisms to homogenize the material, according to Price, as well as recipe-based blending. “Fiber piles should be separated by supplier, so that you can blend accordingly, and manage the feed rates of each of those products into the system,” Price says. “If you have a front-end loader, it might be one scoop of the green and two scoops of the dry, depending on the moisture content. If you’re using bins or hoppers, then you can control feed rates of those coming into the process, making sure of uniform, consistent size coming into the dryer.”

Although every individual particle size won’t be of the same moisture content, Price says, the heat required for the process becomes more homogenized. “For a lot of rotary dryers, when the fiber goes in, the heavy, wet stuff goes to the outside of the dryer. As it dries, it moves down the length of the dryer, loses weight and falls to the center, where the air flow picks it up and carries it through the dryer. If you have a dry particle coming in, it’s not going to stay on that outer ring of the drum dryer very long—it will fall in faster—and the wet material will stay in the dryer longer.”

Sending a consistent product through the dryer it will result in a better end product. “So your key performance indicators are moisture content, routine sampling of raw materials for size considerations going into the dryer, and then comparing that to the heat and energy input—you’ll find what works for that plant to get a uniform drying system.”

When material comes out of the dryer, it should again be sampled for moisture and size. “A lot of times, the material is overdryed, and water has to be added back in ahead of the pellet mill,” Price says. “If you have very consistent moisture content, you can minimize the amount of water you put back in for conditioning.”

As for how often material should be sampled, Price says that if the infeed is consistent—fiber is coming from the same sources, and weather is normal—operators could get by with four to six times per shift. “If you’re getting torrential downpours and your product is stored outside, you’ll want to pay more attention to that, and do it more often. It’s important to get your operators in tune with that, why it’s important, and understand the effects on the process recipe. If moisture content is all over the map, you’ll see it in your pellet—telltale signs. It will form differently, the durability will change and it won’t stick together, and an there will be unbalanced flow through your pellet mill. People tend to focus on size a lot, and that’s very important, but if moisture content is bouncing around, you’ll see the same effects.”

Tracking downtime is essential to minimize it when related to issues caused by inconsistent fiber, according to Price. “If you move from reactive-based maintenance to a more plan-based program, you can start looking at eliminating the short-term interruptions. If a guy goes out, shuts the hopper down, grabs a sludge hammer and beats on it for 30 seconds to keep it running, that doesn’t show up in a downtime report, because that’s become the operating procedure, even though it isn’t normal. When you identify the things that are causing you downtime, you can put in a procedure to prevent them.”

More Considerations

Design/Build

Besides having a person experienced in plant design, an expert process technician is a must, Swaan says, as pellet plants are difficult to operate. “You need someone who’s going to keep it going. We now have years of understanding surrounding what particulate size works best at what part of the process, and that comes down to the experience. A 747 or any kind of aircraft has the capacity to get off the ground itself, but you want a confident team or pilot that know how to fly it, and fly it well, or it will be disastrous. You really have to understand how to stay operating and the dynamics of the process—that’s something you just can’t engineer.”

On the current cost of building new plants or expansions, Stamey says it varies considerably. “We don’t recommend thinking about the construction of a pellet plant in terms of a cost per ton of annual capacity,” he says. “These numbers can be misleading, since there are a wide range of assumptions that need to go into them. Costs can vary greatly depending on the raw materials—a facility supplied by 100 percent dry planer shavings will require significantly less processing equipment than a facility supplied by 100 percent round wood, for example.”

Costs related to site development and shipping and receiving logistics are often underestimated when considering project budgets, but can greatly impact the total capital required, Stamey adds. “A preliminary study where the project is defined and a high-level cost estimate is performed can be done quickly and affordably, and will give you much better information for making decisions.”

Safety

One nice thing about wood pellet production is that nearly all processes within the facility have existed in other wood product facilities for decades Stamey says. “Safety in the production and storage of wood pellets has seen improvement, as well as research over the past several years, as the industry is recognizing some of the unique challenges that pellets present.”

“You really have to understand that you’re dealing with something very explosive and flammable,” Swaan says. “Some of us have gone through explosions and fires, and know there should be someone around the table who is going to give you some guidance on safety, based on references.”

The typical price tag for adequate safety and fire protection at pellet mills ends up being three or four times more than what was initially thought, in Swaan’s experience. “The principles are all the same, no matter how small or large the facility,” he says.

Permits/Emissions

Air permit requirements are constantly evolving for the pellet industry, Stamey points out, so coordinated plans involving permitting consultants and process engineers are more important than ever. Price agrees. “You should be very aware of what your emission factors are when you’re doing your permit,” he says. “You don’t want to have to come back later and add a regenerative thermal oxidizer (RTO). It boils down to environmental engineers, finding equivalent test data and vetting your permitting process thoroughly.”

A developer should consult with engineers and technology specialists that work in the wood products industry, Price says. “As processes become more refined, I think we’ll see testing show we’re getting higher volatile organic compounds (VOCs) out of processes than we expected, and this goes back to drying. Typically, if you’re doing a very good job drying wood products, you’re capturing those VOCs in the dryer. But as you go through the pellet press, you will reach temperatures where VOCs can come off. I expect to see some facilities impacted by this, where they don’t have VOCs reported correctly in their permits.”

Price says that in time, he suspects there will be more regulatory focus on green hammermilling. “Green milling tends to get material into that temperature range for VOC release, so they may look at that, particularly as our industry comes under more scrutiny from an environmental and sustainability point of view.”

As for the tongue-in-cheek that wood pellet production is an art, Swaan says he views it a bit differently. “I think of it as more of a skill,” he adds. “You need a skillset—it’s basically 75 percent technological, and 25 percent skill. If you don’t place importance on the skillset, the other 75 percent doesn’t matter—the plant is not going to operate.”

Author: Anna Simet

Editor, Pellet Mill Magazine

701-738-4961

asimet@bbiinternational.com